Blood Red Death Ray

CHAPTER 1

Birth on the Island of Zug

Blood Red Death Ray sprouted up between sidewalk slabs in River Rouge, a factory town south of the Detroit. Riverfront homes there offered a view of Zug Island, where thick columns of steel-smelting smoke rose from the grunting mills like grey fingers on the hands of the devil himself.

Jane Doe, D-Ray’s bassist, developed her street cred at the age when most girls were selling Thin Mint cookies. When she was still a pre-pubescent waif she was picked up by two police detectives and delivered to Wayne County Child Services when she was found living in the Philosophy room of the River Rouge, Michigan city library. Though she was able to quote Nietzsche, Kant, and Kierkegaard chapter and verse, she couldn’t provide her own name; when asked, she would offer up the names of dead musicians: Kurt Cobain, Tupac Shakur, Jim Morrison, and Terry Clef, a local trumpet legend who had been murdered by a Santa-clad Salvation Army bell-ringer.

Her simultaneous symptoms of short-term amnesia and long-term deja vu, resulting in an inability to remember almost anything not related to music and at the same time believing she’d been there and done that, was recognized by doctors to be the rare condition known as amne-vu. This condition, though unusual, typically causes little disruption to the lives of musicians.

As is customary with the lost, authorities named her ‘Jane Doe.’ The name stuck through seven foster homes and her eventual adoption by Stosh and Betsy Dobrowczky. In interviews years later, the Dobrowczkys would sometimes say that ‘Doe’ was short for ‘Dobrowczky,’ but when they had called her ‘Jane,’ and not ‘Jane Doe,’ the girl would jam her fingers into her ears, tightly close her eyes, and launch into a vocal tantrum, belting out the Canadian national anthem.

Jane Doe and her Jazz Bass

The Dobrowczkys were salt-of-the-Earth southeast Michigan third-generation Poles: Stosh was a Bessemer tech in the All-Burn steel mill on nearby Zug Island; Betsy cut hair part-time at the Alouicious Shag ‘n’ Blo salon. Together, they served up a solid family foundation for their unusual foundling.

After becoming a Dobrowczky, Jane gained her affinity for the low end of the audio spectrum: At night, her bed would bounce room to room from the deep-bump thump of the iron ore crush-pistons operating twenty-four hours a day only a few thousand yards from the family home.

The slender brunette breezed through elementary and junior-high schools. Class work was easy for her, after living in the library, but she especially enjoyed being in the school band. Jane took piano lessons from her aunt Flo, and occasional guitar lessons from her older cousin Donald Dobrowczky, leader of a successful Detroit-area polka band called Obviously 5 Believers. Their specialty was an hour-long set of polkacized Johnny Cash tunes.

Zug Island, home sweet home

By the age of 16 Jane was proficient on guitar, bass, drums, clarinet, violin and accordion. When she was seventeen she created her own YouTube channel, getting twenty-five views in the first 2 weeks. She played all her instruments simultaneously in a blistering rendition of Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” as her initial offering. Her Internet success was a clear sign to Jane that she needed to more tightly focus her wide-ranging talents if she ever wanted to succeed, so she decided to concentrate on the bass guitar.

Jane’s powerful amnesia had blocked all memories of her life before adoption, but she had eventually found that music was the key to her lost childhood. When she played, she entered a place that slowly peeled back the layers of darkness blurring her early memories. When the connection to Jane’s muse was at its most intense, she was able to see her past, and she had been attempting to reconstruct her infancy and early childhood since she first realized the power of music to help her do so.

In 2004, the most popular indie rock band in the downriver area was Dharma Chain; their 2003 self-produced six-song project called “Iron Ore What?” made the band enough money to buy a Walmart PA and a used Dodge Tradesman 100 van. After bassist Bobby Chirmside moved to Florida to start a business herding snakes, Jane nabbed an audition thanks to her cousin Donny, who had once sold a ’59 custom Jose Pecker Accordi-Guitar to the band’s founder: A charismatic singer/songwriter/guitarist from Melvindale named Michael ”Rabbit” Smith. Smith was instantly attracted to Jane’s chops, and more than a little bit attracted to her looks, too … by this time, at 19, she had evolved into a natural knockout.

After Jane joined the band, Dharma Chain took off … within six months they were playing non-stop across the upper Midwest. They traveled in the van, sleeping in the vehicle, on fans’ couches and beds (sometimes with fans in them), on floors, and occasionally splurging on a motel room when they needed unlimited-hot-water showers. Smith possessed a potent stage presence (an early Detroit News review of “Iron Ore What?” called Smith ‘The heir apparent to David Bowie’s groundbreaking performance as Ziggie Stardust spiced with Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong’s power-punk sensibility. The band’s juice was further pumped up by Jane’s exotic looks (she had dyed her hair blue-black and gone crazy with the eyeliner by this time, which really set off her turquoise eyes) and emphatic, melodic bass lines. The band built an enviable fan base.

The Romulus farmhouse

When Dharma Chain wasn’t on the road, they lived together in a worn-in farmhouse in Romulus, Michigan, near Detroit Metro Airport. They built a rehearsal studio in the back bedroom and recorded another eight songs, which they put up on social media. They also had 10,000 vinyl copies pressed. Smith kept their songs short, in part because they usually had to record takes in the intervals between jet takeoffs.

Smith attributed his artistic success to a series of self-help videos called “Divining the Undiscovered You: Melodic Methods to Actual Self-Realizing of Your Omega Doppelganger Spirit,” developed by billionaire mystic mogul and entertainment impresario Rex Tremendae, who had lifted his name from the third section of Mozart’s ‘Requiem,’ an obvious change for someone whose parents had named him Marvin Frankel.

Tremendae operated a New Age spiritual compound in the mountains near Sedona, Arizona, known to initiates as “The Nest.” His holdings included the Arizona Coyotes curling team, Atma Buddhi Manas Records, three-hundred and ninety malls in North America, Europe and Asia, twenty-seven classic Ferraris, and the allegiance of millions of followers. Tremendae saw Dharma Chain as an opportunity to reach out to (and into the pockets of) a whole new generation.

The effects of amne-vu

Tremendae’s little-known background in summer stock musical theater had made a powerful dent in his sensibility. As an understudy for all eleven parts in Sondheim’s “Assassins,” he had slipped a few cogs in his brainbox, and would often slide into an alternate reality in which he thought himself be a parade of Broadway divas. His ‘Melodic Method’ program involved a murky mix of secondhand pop psychology, stolen Native American ceremonies, naked co-ed campouts, and for those who completed the classes, the eventual delivery of a ‘Melodic Method Life Mask.’(Tremendae had been a eBay Power Seller, and had purchased the inventory of a failing vinyl mask factory in Shanghai. He integrated the ‘Melodic Method Life Mask’ thing as a tactic to clear out the warehouse).

Jane Doe, Day 4: Riff still not right

Smith’s ‘Life Mask,’ delivered to him in the original “Hollow-ween HappyTime Mask Toy” box, was a toothy grey rabbit head, and he wore it constantly. Smith referred to himself as ‘Rabbit’ and didn’t answer ever again to the name ‘Michael Smith.’

The highlight of Tremendae’s annual calendar was the Burning Me Festival, held near The Nest in Sedona. Hundreds of thousands of frenzied followers came from all over the planet, and millions more watched the satellite and Web simulcasts. At the end of three days of assorted music performances, punctuated by Tremendae’s spiritual hooha, festival-goers were encouraged to run through one hundred yards of fire to prove that they had raised their consciousness to the level that would allow them to do what they had previously thought was impossible.

Unfortunately for most, what they had thought was impossible really was impossible.

Tremendae invited Dharma Chain to record at his Crystal Feather Hawk Eagle Studios at The Nest, and Jane and the rest of the band followed Rabbit to Sedona, where they managed to lay down eighty excellent songs, despite Tremedae’s lyric recommendations and nonstop suggestions to put “more highs on the lows.” Jane noticed that Rabbit’s behavior was becoming even more erratic than usual, though he was able to deliver on his part of the sessions. After six weeks of recording, the project was complete, and Tremendae prepared to unleash Dharma Chain as a mandatory sacrament upon his thousands of followers (at the nifty retail price of $125 per record, including a bonus astrology chart, with the band getting point-one percent).

During the sessions, Tremendae secretly pulled Rabbit out of the studio, instructing him at the deepest levels in the homebrew spirituality that permeated the place. Rabbit, drunk on a creative bender and stripped of his will, repeated Tremendae’s secret mantra (“I am nothing, you are the wind, and water and sky, Jody”) and simultaneously signed away the rights to the songs, the recordings, and any and all future uses thereof. Jane and the band were unaware of the loss of their treasure.

Rex Tremendae

Three days after the final mix, following a late-night party celebrating the completion of the project, Jane knocked on Rabbit’s bungalow door. Getting no response, she entered, and shuffled through the darkened chamber, her small bare feet bumping against empty Bosco bottles. When she found Rabbit, he wasn’t breathing.

Emergency medical technicians were able to revive and stabilize Rabbit, and he was taken to Sedona Regional Medical Center, where he vegged out in a coma for seven days before he exited this plane. The official cause of death was “Acute respiratory failure leading to brain death due to extended lack of oxygen, fundamentally attributable to toxic levels of Bosco … the milk amplifier.” This was a drink that Smith had begun using heavily after seeing the word ‘Bojangles’ written in the green blips of the regular UFO traffic smattering the Arizona sky. In his increasingly disordered mind, he changed the word into the recipe for his own demise.

After the funeral, Jane flew back to Detroit. For the next four months, she lived off the last of the money she had saved when Dharma Chain was gigging. She couldn’t believe how close she had come to dream-come-true, and how wickedly it had all been taken away.

CHAPTER 2

Rumpus Room Research

One October Wednesday, Tremendae booked a conference room at the five-star Detroit Regency Hotel to present one of his inspirational ‘Divining the Undiscovered You: …’ seminars. Jane lurked in the back of the conference room, unseen by Tremendae, as he sold his program, complete with stacks of Dharma Chain records that were moving at a brisk pace … all proceeds to Tremendae and his movement.

Jane confronted him in the men’s room, where he stood in front of the mirror, running a brush through his extravagant silver pompadour. Tremendae had the appearance of a mid-sixties country singer (think Conway Twitty) stuffed into a Sartoria Domenico Caracenti suit.

“’member me?” Jane Doe said. “Bass in Dharma Chain. I have some tunes of my own. They’re good … as good as Rabbit’s stuff, maybe better,” she said. “Rabbit wasn’t the only talent in the band.”

“Oh, little acolyte,” Tremendae said. “You’re wrong. He was. The only talent, I mean.” Tremendae turned from the mirror, facing Jane Doe.

“You see, you’re not The Rabbit,” he said. “The Rabbit was the actualized Michael Smith, and with my help he evolved into the higher vibration of his mantric harmony, fully in tune with his spiritual Doppelganger.” He put his hands on her thin shoulders, and pushed his orangey-tan face near hers. “You’re not The Rabbit. You’re just a little girl in a men’s room … a little girl in a man’s world.”

Jane Doe’s heart rate increased, her hands balling into fists.

“Want my advice?” Tremendae asked. “Get a job. Find a guy, settle down,” he said. “Play a little on the weekends, if you get the itch. Karaoke, maybe. Better still, forget the music thing.”

“I’m not going to forget this,” Jane Doe said. “Even for me, this is not forgettable.”

Tremendae walked out of the men’s room, down the long corridor to the conference room, stuffed with followers.

Jane drove toward the farm, fishtailing a roar of dust behind.

She put an ad in the Detroit Metro Times: “Singer/guitarist (must do both) and a drummer with monster chops needed yesterday.” She also spent time trolling the downriver Detroit clubs in search of a partner in music.

One night in December 2007, Jane drove to the Rumpus Room to hear Black Pool, a band that had been getting some Detroit media buzz. The singer/guitarist, a sliver of a twenty-something named Deacon, faced the back of the stage for the complete show, sometimes hanging onto the mic stand to keep from falling over.

Deacon had stopped using his last name years ago, but it was recorded on some legal documents relating to his day job of selling ‘no-soliciting’ signs door-to-door. He had buried these in an ammo can in the corner of a field in Melvindale. Inside the can he also squirreled some animal tranquilizers, a couple dozen Mojo condoms, his lucky list of lotto numbers, and a set of night-vision goggles. There was also a picture of someone’s mother.

Deacon lurched into a dead-drunk guitar solo: kerchung, kerchang. It was deadly bad, phoned-in.

“Isn’t he the greatest?” a mascara-marked woman said to Jane.

“No … he’s drunk,” said Jane, as she headed towards the door. But before Jane was able to exit the skeezy scene, Deacon suffered a bout of clarity, and the resulting sixty seconds of vocals and rhythm guitar riffled through Jane like a spiritual lightning strike. Whatever Deacon had been for most of the set was replaced by a blinding slice of brilliance, and it spun Jane into a 180-degree detour leading straight backstage.

The Rumpus Room

Jane found Deacon in a humid chamber at the end of an unattended hallway. He was slouched on a dingy sofa, between a couple of girls sporting tats and tights. Jane introduced herself to him, said that she had been in Dharma Chain.

“I know who you are,” he slurred.

“I’m starting a thing of my own,” she said.

“Really,” he said.

“Really. So I need a guitarist. Who can sing,” she said. “And a mean-ass drummer.”

“Not interested,” Deacon said. The bookend babes giggled.

“Black Pool is ready to go large … we’re about to sign with Horsehead Records in Sioux City … fucking Sioux City … that’s in Iowa.

“Next big thing, huh?” Jane said.

“No, here’s the next big thing,” Deacon said, as he twisted to his knees, ducked his head behind the couch, and hurled the contents of his stomach into the darkness.

“Cool,” said the bookend babes.

“And so, no, to your request, too, Jane” he said, wiping his lips on his sleeve, just before his chin dropped to his chest and an intoxicated snore rattled his uvula.

Deacon

Three nights later, on their return from a gig at the Port Huron QuasiDome, Black Pool’s van was hit head-on by a semi-trailer truck loaded with slaughter-bound pigs. The truck driver had been up for five days, sproinged by Seventy-Two Hour Energy drinks, Vivarin tabs, Twinkies and country music. Deacon had been in the van’s passenger seat, but was ejected from the crash and landed on a steaming, screaming pile of twitchy swine guts. All the pigs, and the rest of Black Pool, bought the proverbial farm, as did the truck driver. Deacon bounced away from death with a sore ankle and a mild case of post-traumatic swine disorder.

The news of the crash brought Black Pool mourners to the scene within hours. Before the bacon-to-be was shoveled up, the uber-geek Hudson brothers trio, by reputation the most passionate Black Pool fans in the state, had erected a ten-foot stand-up likeness of the band, with glowstick halos above the dead members’ heads and a sullen halo-less Deacon kneeling in front. Rudy Hudson decided to honor the hogs, too, somehow blending the whole tragedy into one strange spiritual stew.

He brought a pig mask from the dress-up box in the Hudson family basement and wore it whenever he was feeling particularly lonesome for the band. His brother Dack settled on wearing a cardboard pig nose, and Cal, the youngest Hudson, designed a special day-and-night muscle-pig T-shirt as a method of homage. The Hudsons decided then and there that they would always attempt to be at the side of the last remaining Black Pool band member. They vowed to refer to him as ‘Bacon.’ Deacon, for his part, would eventually refer to them as the ‘Pig Brothers.’

The Pig Brothers weren’t the greatest of the problems that plagued Deacon. His father Stanley (long-divorced from Deacon’s mother, who had left early in their family’s history to pursue an entertainment career connected with counterfeit Mexican boyband paraphernalia) was a constant carrier of chaos in the young man’s life.

The Pig Brothers

Since Deacon had been fifteen, Stanley had been an intermittent occupant of the Pine Rest Christian Mental Health Facility, which he used as something of a hide-out when his exploits as a self-described alien-hunter became too intense. Stanley, whose trade-school qualifications included plumber and electrician, and whose amateur inventor status was clear in his own mind, claimed that the ‘Reptilians’ were orbiting Earth in a spaceship named Betsy, piloted by Commander Hatton.

Deacon had let his father occasionally stay with him in Deacons’ three-room flat above the Shank and Shin Meat Market, a small butcher shop in River Rouge. There, Stanley had developed his plan for the protection of Zug Island against the Lizard People. He armed himself with one bad-ass water cannon: an off-the-shelf Aggressor 7 Super Soaker that he had modified extensively, adding high-intensity ultraviolet LED light bars to reveal reptilian vertical pupils, a 50-watt Radio Shack bullhorn assembly to warn civilians of danger, and a ten-gallon strap-on tank with a high pressure carbon dioxide-charged water delivery system for repelling the invaders, who, according to Stanley, smelled like cat piss and hated water as much as they loved human meat.

When Stanley was in residence, his room had blacked-out windows and was the scene of three-day paranoia-fests during which Stanley would sit in his underwear washing down his meds with endless pots of Spartan coffee. His diversion of choice, when he felt he needed to take a break from Zug-defense plans, was playing all-night rounds of strip solitaire, always winning.

Meanwhile, back at the Romulus farmhouse, Jane presided over a series of unsuccessful auditions, each worse than the last. From the speedmetal tattoo-sponge who had as many teeth as he had strings on his guitar, to the country drummer with a fifty-gallon black hat and a three-ounce talent pool, Jane was beginning to lose faith.

Pup and tub

Finally, after two weeks of getting nowhere fast, she heard a modest tapping at the door. When she opened it, she was confronted by a pair of legs the size of tree trunks, rising to a pair of shorts, encircled with a gigantic belt. The legs were bluegreen and insanely muscular, and terminated in a pair of size twenty-eight quadruple F boots.

A hand reached down, holding a copy of the Metro Times classified section. The other hand held a pair of drumsticks the size of Louisville Sluggers.

Jane invited him in. “Hi,” she said, “My name’s … ummm … ahh …“

“Well, the ad says ‘Contact Jane,’” Pup said, who handed her his copy of the Metro Times. “Are you ‘Contact Jane?’”

“No, just Jane,” she said. “Drop the ‘Contact.’ Where ya from?”

Pup said, “Reno.” As she had never been to that part of Nevada, she thought it possible that the locals were unusual, to say the least. But she had already forgotten whatever misgivings she had developed.

Jane and Pup jammed nonstop for the next two days. Pup was so enthused he forgot to eat. Jane just simply forgot most everything, as was her way.

From the first note, they formed an instant musical bond, and Jane knew that she was two-thirds of the way toward the completion of the band.

CHAPTER 3

Preparations Galore

Thirteen days after the Black Pool van crash, and eleven days after Pup had moved in, Deacon skidded up the gravel farmhouse driveway. Being the object of constant attempted and certainly unwanted accompaniment by the Pig Brothers had taken its toll, and Deacon was overwhelmed to have given them the slip, if only for the present moment.

When Jane opened the door, Deacon said, “Fifty tons of wrong-way pig shit didn’t kill me. I suppose I can survive being in a band with you.”

“Who the fuck are you?” she yelled, and clocked him in the nose. He dropped like a rock. Jane pulled off her left sock and sopped up some blood from Deacon’s schnozz.

Deacon came to in about fifteen minutes, with his guitar across his lap, plugged into a Fender Vibro Champ amp. Jane’s clotting sock was lying across his face. Pup was sitting on the sawed-in-half 55-gallon hazmat drum that served as his drum stool, staring at Deacon. Jane was writing furiously in a notebook.

“Sorry about that,” she said, looking up. “Forgot who you were for a second, then I realized I’ve done this before. Amnesia thing I got, since I was a kid.” She smiled at Deacon, peeled the sock from his face, and put it back on her foot.

“Whatever, right?” she said.

Pup leaned nearer to Deacon, looked at him closely. The floor bowed and creaked. “Black Poodles”, Pup said.

“No, dude, Pool, Black Pool” Deacon said. He closed his eyes, shook his head slowly. “Where’s this guy from?”

Pup shot a stare at Jane, as if he had a particular answer in mind. “Reno,” she said.

“Oh, like that answers it,” Deacon said.

Over the next sixty days, the three of them practiced nightly. They learned fourteen of Jane’s songs, twelve songs written by Deacon. Pup contributed the grooves to another set’s worth of co-written material. Though Jane and Deacon were in a constant state of tension around each other, it all melted away when the music started. The sound was amazing … the musical telepathy was spot-on. This band was ordained.

Deacon and Vic (1948 Vic Damone Strat)

But ‘this band’ needed a name. And though they’d been spending twice as much time batting around band names as they had polishing the tunes, so far, nothing.

One afternoon the front door swung open, and Stosh Dobrowczky walked in, hugging a couple of foil-wrapped bowls. “Got some real foods for you guys here,” he said, putting the bowls on the coffee table. “Homemade ozor zeberka, that’s good old-fashioned blueberry pork meatloaf, and a big lump of twarog … beaver cheese, of course.”

Pup’s eyes got bigger than usual.

“But I gotta run,” Stosh said. “Your mother’s in the car,” he said, looking at Jane. “She’s gonna take me to K-Mart and buy me some pickle Jello,” he laughed. Stosh looked at Pup, raised his shoulders in a ‘what-are-ya-gonna-do?’ gesture. “So we just stopped by to make sure you guys was gettin’ some decent nutrition.” Stosh kissed Jane on the top of her head and walked out the door.

Pine Rest

Deacon, sprawled in the orange La-Z-Boy recliner, said, “The last time I saw my father was in the day room at Pine Rest Christian. ’Bout a month ago. He was sitting in a plastic chair, 100cc thorazine drip on board, mumbling about Commander Hatton’s starship Betsy, orbiting Earth with the ‘lizard people.’” Deacon started to gather steam. “Dad would rub his temples, tuning in a phantom frequency to avoid mind control. I really didn’t know what the hell to talk about, so I told him I was in a new band and we were looking for a name.”

“He started singing, waving his arms around. Nurses ran in, yelled ‘It’s time to go,’ and held him down. I started to leave, got just outside the room,” Deacon said. “The old man looked up, smiling, like he wanted to tell me something important. They closed the door, but I could see him through the window and read his lips.” Deacon’s voice got lower and slower. “Blood red death ray.”

Deacon’s eyes rolled back into his head, and a rattly snore started up.

Blood Red Death Ray

Jane stared at Pup, Pup stared at Jane. A light went on: a glimpse of the future.

Above, a Northwest 737 Max turned on its final approach into Detroit.

As the rehearsals moved forward, Pup’s drumming was becoming otherworldly, and he began to exhibit an unexplainable proficiency in electronics. On a hot Wednesday night, Deacon’s Vibro Champ amp retched into flames after he decided he wasn’t loud enough, and re-wired the audio input of his amp directly into the farmhouse fusebox. A quart of beer put out the fire, but he had blown the speaker, and practice ended for the night amidst the reek of toasted Tolex.

The next morning, Deacon and Jane discovered that Pup had repaired the damage. On closer inspection, they found that he had rebuilt the amp with 12-gauge copper wire and power tubes handmade from jiggered-up Mason jars. Deacon fired it up, slashed a few chords, and it was better than new. A peek through the grill revealed a cat-skin speaker re-cone job … with a little fur around the edges for style. Soon, posters for Punkin the lost cat appeared on power poles in the area.

Pup puts down some astro paradiddles

After the band had worked up enough material for four good sets, Jane called her cousin Donald Dobrowczky, whose polka band had broken up years before, but who had since developed a thriving and far-flung talent booking agency that had successfully booked hot regional acts such as Meelo the One-Legged Break Dancer and V.V. Hotel, a spoken-word artist who was accompanied by a theremin-playing rhesus monkey. It was Donnie who booked D’Ray into their first real gigs: The annual Return of the Vultures picnic in Hell, Michigan, and a few weekends at the Rumpus Room in Melvindale.

Donnie and D’Ray also organized an underground show at Detroit’s derelict Eastown Theatre, where, in decades past, Motor City rock fans had heard Spitsucker, Veevol Sneet, Cow Cow, and even The Pinups, before Doreena had left the band. This gig proved to be the most lucrative: The band brought home over five thousand dollars from their cover charge and from the refreshment concession, which was managed by Stosh, who put brewery decals on his arms and encouraged people to yank ‘em for brew … either Heineken (“Fuck that shit,” he’d yell) or Pabst Blue Ribbon. After the success of the Eastown gig, they organized three more underground all-nighters, and were able to sock away $7,500 in cash, which they stored inside the stainless steel cranium cap that crowned their drummer’s head.

One morning, Jane saw a YouTube video promoting Rex Tremendae’s annual Burning Me Festival in Sedona, Arizona. The video featured several staffers of the concert, including Bobby Chirmside, Rex’s new stage manager, Dharma Chain’s old ex-bassist, obviously retired from the Florida snake farm, and recovering from ophitoxaemia: venomous snake bites.

“As long as we get there before the concert starts, we’re golden,” Jane said. “Bobby can sneak us onstage for at least one song, for sure,” Jane said. “Good thing he’s gotta lot of experience handling snakes … he’ll need it working for Rex.”

Deacon wasn’t convinced about going on the road, because he was still nursing a pretty serious case of post-traumatic stress as a result of the deadly Black Pool van accident, and the idea of traveling cross-country was not a pleasant one.

Jane encouraged him by appealing to his not-insignificant ego. “We’ll be making the World’s Longest Music Video, featuring you, Deacon. But it needs to have some character … I don’t want to shoot the whole thing on my phone like every other wannabe influencer. It has to an homage, a pastiche, a nod to the greats, like Sergio Leone.”

Deacon thought for a minute, his eyes rolling back a little in their sockets. “I know, get this!” he said. “We can use my dad’s sewer camera.” Deacon said.

“It’s not exactly HD,” Jane said.

Pup chimed in, “When I’m done with it, it’ll be 3D.”

“OK, I’m in,” Deacon said. “Do we gotta come up with the world’s longest song, too?” Deacon asked.

“Nope,” Jane said. “I’ll remix and edit all the music from our shows on the road into one big song. We shoot the whole trip … gigs, the road, everything we do. Put the camera on a mic stand, or maybe ask a fan to film some, too.”

“Assuming we have fans, “ said Deacon.

Pup had been good-to-go on the trip from the first mention of it. He was ready to get out of the area so he could escape the scrutiny of the neighborhood children; he was beginning to feel overwhelmed with the crop of lost kitty reward posters everywhere.

They got ready for the road with a vengeance. Jane decided that they would follow Route 66 to Sedona … that ‘Mutha Road,’ she called it … and she drew their route on a map of the United States that she had pinned onto the wall of their bedroom-studio.

The Moogobs L13 sewer cam

Deacon had been wrestling with the effects of his liquid intake, and knew that he wouldn’t be able to continue to assault his consciousness and body with toxic beverages. So, with a quiet determination that even he hadn’t known he possessed, he poured out the remaining brews that he had stashed under his bed, and made a vow to stay on the wagon while the band was on the road.

Sadly, there were other, more toxic influences that would find him in the coming weeks.

There was only one other problem: neither Jane’s nor Deacon’s vehicles were sufficiently roadworthy. But when Jane mentioned the problem to her cousin Donny, he had a solution.

“Tell ya what,” he said, in a late-night phone conversation with Jane. “You can take my Caddy and trailer combo. Thing is, I’m a little behind on the payments, so I’m expecting that it’s gonna get a visit from the repo man pretty soon, anyway. I’ll bring it over to your place, you can hide it in the barn while you get ready to go, and I’ll claim it was stolen. Then you can just hit the road.”

“Stolen? What? Uh, what if we get stopped?” Jane said.

Another look at the band

“Don’t worry about it,” Donny said. “You won’t remember this conversation in five minutes, much less five hundred miles down the road.”

And the next night, Donny arrived with his heirloom 1950 Cadillac Coupe de Ville, pulling a 1964 Airstream trailer. He backed the vehicles into the barn and shut the door tight.

Knowing that Pup’s weight might be something of a strain on the suspension, Donny suggested that they consider some alterations. Pup worked for several nights before he called Jane and Deacon into his improvised workshop. They were amazed at what they saw:

Pup had tweaked the engine to perfection, increasing the horsepower by fifty percent with a homemade turbo, cold-air intakes, molybdenum hi-temp glow plugs, and twin fuel heaters. He built a miniature bio-Diesel conversion plant into the trunk, so they could run their new Hybrid Caddy on suntan oil and road kill. He reinforced the suspension with adjustable hydraulics to support his weight. The Caddy hummed in anticipation of the road.

As a final touch, Pup glued a pair of bobbleheads on the dash … one of Chuck Berry, and one of Blind Willy Johnson, his mentors.

Jane and Deacon: The Sink Sessions

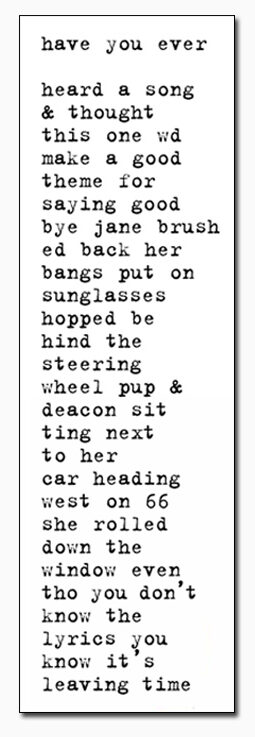

On July 4th D’Ray finished packing the trailer with their PA, instruments, the sewer camera and provisions. Deacon slid into the passenger seat, dropped his shades over his eyes, and slouched low. Jane sat behind the wheel, her head clearing the dash by about six inches. Pup eased into the back seat, and the Caddy groaned a bit under the weight, but he popped a chrome toggle switch a couple of times to bring the rear-end hydros up. Jane raised the canvas convertible top once Pup had settled inside, and the World’s Longest Music Video Roadtrip was underway.

Deacon asked Jane to swing down to Melvindale on the way west so he could pick up something up that, he said, “Goes everywhere I go.” They waited at the curb as he dug up his ammo can and stashed it in the Airstream.

CHAPTER 4

Get Yer Kicks on Route 66

The four hours to Chicago passed in what seemed like minutes. Donny Dobrowczky had booked the band into the grand opening of the Cave, a suburban club built into a strip mall on the far west side of the city. The owner of the bar, Norman Woo, had once been a partner in a company that had invented an expanding gel for use as a low-cost Botox alternative. The product had actually made it to the market, and was being sold under the brand name Furrowfree, until the foreheads and lips of early customers began to explode.

Woo was left with thousands of gallons of the goo, and pending class action lawsuits. So that he could get some value out of the stuff, he decided to coat the inside of a former Red Lobster with it, creating a drippy funhouse stalactite ambience that had the added benefit of intense sound insulation. He had even created lumpy off-centered tables and matching chairs with the last of his chemicals.

D’Ray started playing, and something sounded unusual. At levels that were normally plenty loud, they could barely hear each other onstage. Jane shrieked her vocals, Deacon turned up his amp to the max, and all they got was something like the level of a clock radio on two.

No one in the club could hear the band … the gel sucked up the music so well that no sound traveled anywhere. In the back of the club, a familiar trio chanted, “Turn it up, Bacon … turn it up, Bacon … TURN IT UP, BACON.” Deacon couldn’t believe that the Pig Brothers had found him in Chicago, and he turned his back on the audience for the rest of the set.

At the first break, Woo asked them to turn it up. Deacon told him that it WAS up … all the way up. Pup slipped out the back door, and returned a little late for the second set, just as Deacon and Jane were about to announce that the gig was cancelled because the drummer was AWOL.

Pup returned carrying new pieces for his kit: a 30-gallon steel drum, and an orange passenger door from a 1970 Chevy Vega. He was louder, but not enough, and the formerly packed bar quickly emptied.

Woo shrugged his shoulders after the second set, and said that he was “Gonna have to re-think this Woo-Goo insulation thing.” He paid the band half what they were expecting; it was hardly enough to keep Pup in tacos for the night.

The Pig Brothers stood at the curb as the band drove off, shouting, “Black Pool, Black Pool.”

WEEK TWO: SPRINGFIELD, IL.

The Rainbow Lounge was situated on four acres of scrabbly ground a few miles south of Springfield. Years before, there had been a thriving tourist court on the property: six twelve-by-twelve cabins, each painted a different color, inside and out. When the interstate ripped the guts out of Route 66, the tourists stopped coming, and the owner converted a former office building into a Dairy Lick ice cream joint by day and a small, hard-drinking bar by night. Deacon stayed in Red, Jane in Yellow, and Pup in Blue.

On Friday night after the gig, Deacon took advantage of the privacy and invited a couple of local girls to, in his words, ‘Viddy a premier of tonight’s concert footage and, after that, check out my collection of bootleg Velvet Underground vinyl, with Nico and everything.’

Photo of D-Ray stage plan (after going through the wash in Deacon’s jeans).

With the assistance of Tiffany and Cynthia, Deacon raided the Rainbow Lounge kitchen, scoring two handles of Ghirardelli Black Label vodka and a quart of Gatorade. He gathered up his remaining souvenir condoms (stashed away for several years in his ammo can), but forgot to grab his common sense. Without the latter, there was not enough Deacon left to prevent being overrun by Ernesto, a full-blown wacko alter-ego who, after punching several holes in the walls with his tongue while wearing nothing but a black leather guitar strap, got a good start on a self-inflicted butt-tattoo depicting either Edgar or Johnny Winter. Although the first action caused some initial interest on the part of the girls, the latter event caused them to dash into the night without various and important bits of clothing. Deacon/Ernesto then proceeded to trash the cabin such that it ended up several inches off its foundation.

When Jane pounded on the crooked door in the late morning, Deacon slithered over to open it, and sat on the bed as she looked around incredulously.

“What the hell happened here?” she asked.

“Songwriting session,” Deacon said. He tapped his forehead. “It’s all here. Calling it ‘Gator in a Red Room.” Deacon focused on Jane. “Truth is, I had to quit drinking. Alcohol. Maybe you hadn’t noticed? Anyway, I’m doing the chocolate cure. All kinds. Bring it on.”

Jane pondered this vague proclamation. Her memory of Rabbit and his Bosco-induced demise should’ve been a red flag, but that memory, like so many others, was buried deep in her inaccessible mind-parts. She was happy enough, though, to know the reason that Deacon had been something other than impaired since they had left Romulus.

Jane Doe in the lyric-writing groove. More great lyrics soon to be lost to shower steam.

After the first set, three men dressed as golf pros walked up to the stage. One wore a cardboard pig nose, one a muscle-pig T-Shirt, and the third a full-face pig mask. And, as they had days before, they called Deacon ‘Bacon.’

Instead of losing it, Deacon decided that there was no point in antagonizing this trio, so instead, he reached into his ammo can, stashed, as always, behind his amp. He yanked out a wrinkled envelope with a sheet of yellow legal pad paper within. There, in long, neat columns, were Deacon’s lucky lotto numbers, which he gave to the Pig Brothers.

“Take these numbers, win some cash, book a flight on Aeroflot and send me a postcard from Des Moines,” he said. “Beautiful this time of year, I hear.”

The Pig Brothers snorted in appreciation.

With that, he hoped, he might have broken the co-dependent connection that had existed between him and them. But no.

WEEK FOUR: JOPLIN, MO.

Deacon had been talking about finding the birthplace museum of Janis Joplin for hundreds of miles before they arrived, and even Jane’s insistence that the name was just a coincidence did nothing to chill Deacon’s enthusiasm for finding a connection to one of his rock heroes.

“Janis could drink like a fish and still deliver a pretty solid ‘Respect,” he said. “My kind of woman.”

Jane said, “Um, I think that was Aretha Franklin.”

“Whatever,” Deacon said.

Poolside at the Joplin, Missouri Moose Lodge

The Joplin gig was booked at the Moose Lodge, and the owner of the place, Saul Lums, had insisted that the band wear special Moose Lodge antler hats as a sign of honor to the association.

“No hats, no gig,” Saul said.

Ever the realists, Jane and Pup were agreeable, because they wanted the money. Deacon refused. Pup gave him a look that suggested that Deacon’s head would wear an antler hat whether said head was attached to Deacon’s neck or not. Deacon got the message.

They wore them all night, but Deacon renewed his old Black Pool habit of playing with his back to the audience. The video showed his skinny frame topped with a Bullwinkle chapeau in the semi-darkness of the rear of the stage.

Still facing the rear, Deacon told the crowd that Joplin had been a big disappointment to him, and that he probably wouldn’t be playing there again. Some of the folks in the audience looked at that statement as a promise they hoped would be kept.

The owner let them keep the antler hats.

On the way out of town, Deacon said, “We should play someplace where they would really appreciate our music … like Japan.” Deacon turned in his seat, looked at Jane.

“Seriously, man,” he said. “I’ve always wanted to see Godzilla.”

Jane said, ”Hate to tell you this, honorable Deacon-san, but Godzilla is fucking make-believe.”

Deacon took a swig of his 40-ounce Yoo-Hoo.

“Monster bad news,” he said.

D’Ray was booked for a weekend gig at the Disney, Oklahoma Naked RockWall Weekend, a monthly gathering of motorheads who love nothing more than driving their outrageous Jeeps and other tricked-out four-wheelers over formerly pristine landscapes while their junk waggled in the breeze. Here, the crowd was all about D’Ray, who rocked with a vengeance. Deacon tapped into his pent-up frustration over the Godzilla disappointment, and his fire was contagious.

After their show, Deacon and Jane sat on a bluff watching the vehicles climb nearly vertical walls of rock with completely naked drivers, slide down waterfalls, and generally defy gravity while completely tearing up the terrain. Pup had claimed fatigue and retired to the Airstream. An hour or so after his exit, Deacon and Jane spotted their Caddy, without the Airstream, in line to challenge the Wall of Pain, the four-hundred foot tall obstacle that only a few have ever conquered.

Deacon quickly worked out a few wagers with some nearby spectators, assuming that Pup had good reason to unexpectedly join the competition.

The Cave, Springfield, Illinois

When the green light flashed, Pup and the Caddy flew vertically up the wall in four-point-seven seconds, overshot the platuea by three-hundred feet, and glided back down to land safely next to the camper and the rest of the band.

Turns out, Pup had ‘borrowed’ a General Electric turbojet powerplant from a T-38 Talon fighter that had been mothballed at the nearby Disney Air Force Museum, strapping it onto the undercarriage of the Caddy. His little mod added about two thousand pounds of dry thrust to the car.

Deacon won over three-thousand dollars from his wagers, after which D’Ray had to beat a hasty retreat to avoid some pissed-off rednecks who felt that the bets had had been fixed, in the sense that all the other drivers in the competition had actually been human. The thing is, they didn’t mind the addition of the jet engine … that, they admired.

WEEK SIX: AMARILLO, TEXAS

D’Ray played a weekend gig at the Amarillo Airport Carriage House, situated directly in the flight path of Runway Three-W (which is actually the only runway at the airport). The sound of the landing jets had a weird homesick effect on Jane, who started acting strange in the middle of the second set on Saturday night. Between songs, she started spouting quotations from the great philosophers, which the crowd found to be increasingly more puzzling.

Amarillo airport. Fast and convenient .. no TSA

“Nietzsche said that ‘A pair of powerful spectacles has sometimes sufficed to cure a person in love,” she said, and the crowd gave up a few “right on’s and “tell it’s’. “And he also suggested that ‘In music the passions always enjoy themselves.’”

“Woo HOO,” said the crowd, a little more subdued this time.

“And Soren Kierkegaard said, ‘Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards,’” Jane said. “And, I believe he nailed it when he postulated that ‘It’s so hard to believe because it’s so hard to obey.’”

Onstage, Pup and Deacon looked at each other and shook their heads. Deacon walked over to Jane’s drink, sniffed it, and finding it to be non-alco, took a gulp, hoping for some of the same enlightenment that she was apparently enjoying.

And that’s how the rest of the night went. A couple of songs, the occasional sound of a jet, and then an outpouring of philosophical intelligence recalled from Jane’s childhood hiding place. The crowd loved the music … all of them all had, since the very beginning of the road trip, but their eyes glazed over with the between-song banter. In the last song of the set, Jane played the best bass solo of her life.

The sewer camera caught it all.

CHAPTER 5

The Great Doe Hunt

On Sunday afternoon, when Deacon and Pup woke up in room 123 of the Amarillo Airport Carriage House (one of the benefits of playing motel gigs was the perk of a free room, which they always shared), Pup on one bed, with the frame pushed to the floor, Deacon on the rollaway, they looked over at the odd-shaped bodybump under the blankets of Jane’s bed, and, when the fog lifted from Deacon’s grey matter, he realized that she wasn’t there. And Jane’s bass case wasn’t on the bed next to where she also wasn’t, and when they looked out the window to the Caddy, she wasn’t there, either, though the Caddy was. Her laptop was on the table.

Deacon used the laptop (with Pup’s assistance) to do a search for ‘Jane Doe,’ but ended up with 40,000,000 hits: obviously not an easy name to get specific with. The boys checked out and got back on 66, headed west, toward their next gig. Deacon figured she might have gone there.

Pup spun the radio dial as Deacon drove, and passed a station from Juarez, Mexico that was playing an all day Menudo marathon. Deacon skidded to the shoulder. He knew what to do: Call his mother, the boyband-cartel mujer. She might have some insight into why an amnesiac female bassist might suddenly disappear … she had been a disappearing act herself, Deacon thought.

And the call bore fruit. Through channels, she discovered that members of the rival Juarez cartel had gotten their manos on Jane in hopes of attracting Deacon, and through him getting his mother to cough up pesos by the buckets. And so, Deacon and Pup steered south to Juarez, and the hacienda of Rachel DeeDee Ramirez La Puente.

They drove all day, stopping for snacks along the way, and filling up the tank with discount suntan oil and freeway-flattened possums.

They arrived. Dangerous-looking men patrolled the outside of the house with automatic weapons, dressed in matching garish undersized sequined jumpsuits. Thick steel bars protected the window.

Deacon spoke to the man nearest the door, who knocked a secret knock. The door opened, and a woman threw her arms up in the air, then wrapped them around Deacon in a long hug. Soon, he came back to the Caddy and drove it around to the rear of the hacienda.

Inside, the house was cheery, if a little fortress-like. Deacon’s mother offered them dinner, and as they ate, she filled them in on the situation. It was true, she said, that Jane had been kidnapped by bloodthirsty men who would stop at nothing to put Rachel out of business, and she knew what she must do to reunite her son with his bassist.

Mom’s place

There were three major cartels competing for the business of smuggling counterfeit boyband merchandise into the United States, and things were getting ugly, according to Rachel. Esteban Sonofrio, who had sung in the band ‘Mucho Gusto’ from 1990-95, ran the Juarez Cartel. The Gulf Cartel was under the direction of Ricky Rohimbo, the famous front-boy of ‘Muchachos de la Moles’ from 1982-92.

The Sinoloa Cartel was the business of Rachel, whose men had dug a tunnel from the bottom of a Days’ Inn swimming pool in Juarez, under the border, and into the basement of the evidence room of the El Paso border patrol office.

The other cartels had their own smuggling methods: The Juarez Cartel utilized surplus Predator drones to drop bales of bubble-wrapped records and posters into the States, and the Gulf Cartel specialized in the use of second-hand narcosubs purchased at a deep discount from the DEA.

One surprised Pup

Even though the market was huge, and it seemed that there would be enough business for everyone, it was not uncommon for people in opposing cartels to disappear, only to re-appear in several different locations simultaneously.

Here, ‘getting ahead’ might mean success, or it might mean receiving a cooler containing the severed noggin of a colleague, who, because of the power of “Magia mexicana” (Mexican magic) continued to serenade.

Rachel made a call to the men who held Jane, and told them that their ransom demand would be met. They agreed to bring Jane to Rachel’s hacienda in an hour.

Just as they were finishing their meal, the soothing outside cricket-song was punctuated with the sound of car tires on gravel … the loathsome Juarez Cartel soldiers had arrived.

Rachel pulled a Heckler & Koch HK PSG-1 sniper rifle from under the couch and slammed a magazine into it, just in case the deal went sour. She yanked a peso-stuffed pinata in the shape of Dave Gahan from the closet.

“Mom, wait, before this goes any farther,” Deacon said. “I have something to give you. Been carrying it forever.” He reached into his ammo can, and handed her the picture of her as a young woman. She took a peek at it, spun it into the air, and pumped a round right through the center of it the photo.

“Always hated that picture,” she said. Then she walked to the front door with the pinata in tow.

Deacon, stunned by the gravity of his loss. Or just stunned.

Taking the matter into his own ham-sized hands, Pup was out the back door. Bursting into a diversionary a capella chorus of the Mexican national anthem, he careened through the yard, pouncing on the momentarily immobilized pistoleros in a whirling Puppish Whack-a-Mole jamboree.

The gangsters who weren’t annihilated were scattered. When the deed was done, he walked back into the house with Jane under his arm, and set her gently on the couch. Then he ate three more tamales, and issued a thunderous belch that was in fact heard in Chihuahua.

Rachel looked at Pup, and at the devastation he had caused in the yard.

“Guess you won’t ever have to worry about getting paid for your shows,” she said, not knowing about the antlers and the trampoline tickets.

With a warm adios, the band climbed into the Caddy and drove into the Mexican night, a roostertail of gravel spraying the cool smoky air.

After an uneventful drive, D’Ray had nearly reached Albuquerque. The detour to El Paso and to Mexico had cost precious days, and they needed to step on it to get to the Burning Me concert in time to meet Bobby Chirmside. He had agreed to use his position as festival stage manager to get the band onstage.

Without so much as a warning light, the Caddy lurched and the engine hacked a sputter. Pup got out, raised the hood, and after a minute looked over the top.

“We’re out of possum, right?” Jane said.

Pup nodded his head.

About a mile away, in the desert distance, burned the sodium lamps of a camouflage-painted RV. Deacon and Jane walked to the light, leaving Pup to guard the Caddy.

When they knocked on the door of the trailer, a familiar voice answered, ”What’s the password?”

“Dad?” Deacon said.

The RV door flew open. “That’s right!” he said.

It was Stanley.

“I intercepted a message, son. They’re on the move, those reptilians, and so am I, so am I. Been tracking them … lots of garbly chatter on the burst frequencies.”

Jane Doe, black-and-blue period

“That’s awesome,” said Deacon, as he rolled his eyes.

Deacon explained their acute lack of roadkill fuel for the Caddy. Stanley, ever the inquisitive inventor, was excited about the alternative go-juice system that Pup had rigged, so he offered to load trashcans of dead possums and armadillos onto to top of the RV and drove them back to the car.

On the way there, Stanley told Deacon how he had escaped from Pine Rest Christian with the assistance of a compassionate transgendered nurse named Reggie Bush, who had given Stanley the keys to his/her late father’s Winnebago.

Pup shoved the decaying possums and armadillos into the tank, and soon they were all safe back at Stanley’s place, where they shared a meal of banana coffee stew and cactus leaf pudding with crushed Bayer aspirin topping … Stanley’s favorite meal.

After dinner Pup stayed busy fashioning new percussion equipment from the junk that littered the property while Deacon, Jane and Stanley sat on the porch listening to the coyotes howl. Stanley powered up his portable CD player and slipped in a rare bootleg CD of his favorite music: the psychedelic rock band The 13th Floor Elevators. Jane had a D’Ray CD in the Caddy, and they played it for Stanley, who said it reminded him of a Chinese watch that he had bought in Belgium.

When the last tune finished, Stanley began to talk about his theory of the Earth’s infestation by Commander Hatton and the Lizard People: Horrendous aliens who have been swarming around for millennia, and who were likely getting nearer to their moment of conquest.

Deacon and Jane watched as Stanley went into the RV and took a homemade weapon off a rack on the wall: his Aggressor 7 Super Soaker water cannon, extensively modified to melt the reptilian foe, who, he claimed, avoided water. He proudly showed it off, sending a stream of hyper-compressed liquid ammo shooting sixty feet into the hot desert night, while an LED spotlight shone on the desert sand. Through the PA, he shouted “Adminitio subgisto tergum,” Latin for ‘Warning: Step back.’

Deacon in his happy place

When asked about the composition of the yellowish liquid inside, Stanley said, “I bury cow horns full of manure in a chili field during an ascending moon, dig them up and make a ‘dragon tea’ from the contents by spinning it clockwise in water for over an hour until a vortex forms. Then I drink a pint and hope for the best.”

With Jane tapping her watch, Deacon realized that they had to leave if they were to get to Sedona in time to sneak onto the stage with the help of Bobby Chirmside. They called Pup in from the machine shed, where he had made some new cymbals from tin roofing and a Ford Farmall tractor fender.

They said their goodbyes to Stanley and headed west toward Sedona. About ten miles from Stanley’s trailer, they stopped at a Circle K to buy supplies and Jane realized that she had forgotten the sewer camera. They sped back to the RV.

When they arrived, Stanley was gone, and so was the Aggressor 7 Super Soaker. Jane found the camera where she had left it, next to the old Philco Predicta television; she hit ‘record.’

They heard a shimmery buzz from the desert, and, going behind the RV, they saw Stanley, about a hundred yards out, bathed in a black light that was coming from a stationery airborne craft. They hopped into the Caddy and sped toward Stanley, pulling up about twenty feet away. Stanley’s weapon was pointed at the saucer.

The craft appeared to be huge, and very far away. There was no sound at first, but the roar of its engines increased quickly to an overpowering blast of white noise. Oddly, as it came nearer, it didn’t get larger … and when it landed about three feet in front of Stanley, it was about the size and shape of a toilet seat. A tiny hatch opened with a faint hiss. Stanley jumped back and dropped to a crouch, the Super Soaker trained on the craft as a line of toothpick-thin, half-inch-tall lizard people marched out. Stanley took aim and fired a stream of water at the miniscule creatures, scattering them.

Outside Albuquerque

Instantly, they began to grow, like fast-motion compressed sponges, until dozens of them stood facing Deacon and Stanley. The aliens were about twice the size of Pup. The largest lizard, the one that Stanley called Commander Hatton, was clearly a different species than his minions: He appeared to be a equal mix of lizard and human.

Hatton spoke in a dialect that sounded as if he had studied a multi-language mashup Rosetta Stone audio book … a dialect similar to Swiss Chinese.

“We come in pieces … no, in peace” he said. “From what you call galaxy Abell 1835.” Hatton offered an explanatory smile. “We call it Reno.” The lizard-man began to pace, revving up his presentation.

“There’s no music there, and we never knew what we’d been missing, until your Voyager space probe crash-landed. Almost a total loss … you should have seen the scratches on the golden record.”

Stanley, Jane and the rest of the band eased up a bit, as the reptilian pored into his spiel.

“Using the golden record as a model, we tried to play, tried to sing,“ he said, “But it’s just not in our … our …” Hatton reverted to his native speech, which in this case included a series of teeth-clicks and wheezes, ending with a small jet of red smoke coming from eyes.

“You’d call it DNA,” he said.

Pup, sans drums

Hatton said, “We made use of …” and here he emiitted a burst of barks that sounded like a Doberman in heat … “We call it the Kaamtovin Cube … it’s something like your Ouija board.” Hatton’s voice lowered to a conspiratorial hiss. “As the golden record played, the oracle spelled out these letters: ‘N-K-O-T-B.’”

Hatton continued, explaining how Pup had been created to be the musician that none of them could be. Obsessed by the magic of Chuck Berry’s and Blind Willy Johnson’s music, Pup had bolted from Reno to find his mentors.

Hatton shined a light onto the dash of the Caddy, illuminating Pup’s iconic bobbleheads … he recognized them as the objects of the drummer’s quest.

“And now that he’s found them,” Hatton said, “We’d like to borrow Pup back.”

Hatton asked Pup in his native tongue if he had completed his mission. Pup smiled, and shook his head in the negative.

“Fine, stay here, then.” Hatton continued. “Uber when you need a ride home.”

Snapping his fingers, Hatton summoned one of his lieutenants, who brought forth a CD. “Using the ultimate code as a guide, we combed your planet … And look what we levitated from a flea-market in Albuquerque,” he said. Handing the CD to Stanely, he said, “Put THAT bitch on your player … and observe.”

Pup grooving to the lizard line-dance

A disco-pop track jammed into the humid desert air. Breaking into synchronized dance, the lizard line-up started to perform a spot-on rendition of the New Kids on the Block ‘You Got It (The Right Stuff)’ dance routine, exactly as it had been done by Donnie, Mark, Dannie, Jordan and Jonathan way back when. As they danced, they shrunk back to their original size while kicking it the skeezy.

Jane looked at Deacon and mouthed the phrase, “What the fuck?” Deacon didn’t see her message, though, because his eyes had rolled so far back into his head that he could see yesterday.

As Hatton diminished in size, he said, “We might not be able to sing, but we dance just as good as we want.”

When they had all completely shrunk and filed back into their craft, the little disk shimmied, roaring off into the blackness.

Stanley started jabbering anxiously about the reptilians and their dancing skills, while Jane pointed the sewer camera on him, doing a slow fade. When they got back to the RV, Deacon ran out to the Caddy and pulled his small bottle of animal tranquilizers out of the ammo can.

“Here, Dad. Think you need these more than me,” he said. “Wash ‘em down with a little dragon tea.”

CHAPTER 6

Bringing it Home

The natural bowl of sand that held the Burning Me Festival was crammed with seventy-three thousand music fans, spiritual seekers, artistic free hearts and their pals. Music blared from flying stacks of JBL VerTec VT4889 line array speaker cabinets, hanging from the gigantic stage rigging.

The audience was whipped into a froth of anticipation. The Milky Way smeared across the blue-black sky, and the rank odor of community rock basted everyone in its sweet funk.

The sound of a kick drum and a droning minor chord from a distorted guitar punctuated the desert night.

The shimmering shake of a kick drumhead, rippling with each smashing thump, increased in volume until the mountains almost shook. On the front of the kick drum there was the likeness of the captain of the Starship Enterprise, the venerable James T. Kirk, with x-ed out eyes. Below the image was the name of the band: ‘DoneKirk.’

DoneKirk’s singer was dressed in ‘60s vintage Federation uniform pants, his chest bare, and his orange dreads falling across his shoulders.

And in the audience, heads whirled, sweat-soaked hair flipped like whips, glistening skin reflected the stage lights above. Hundreds of thousands of heads were bopping, arms waved, the whole mass of humans swayed in one dance, glued together by sweat and music, frenzy and exhaustion. This is what they had come for, and DoneKirk was delivering.

Past the back of the crowd, and up the long black hill that formed the back of the bowl, sat three figures: Deacon, Jane, and in-between, propping them up, Pup. Behind them, engine ticking as it cooled, sat the Hybrid Caddy and the Airstream.

Pup was watching the stage through a telescope mostly concentrating on the drummer; Deacon stared glumly at the stage through his night vision goggles, which were amplifying the lights a thousandfold; Jane was clacking on her laptop.

Deacon looked at Jane, glowing green through the goggles. “This is about as close as we’re gonna get,” he said. “We’re too late. We missed our shot.”

“Looks like a Drum Workshop Collector’s Series double kick set … Blood Red sparkle,” Pup said. “What are the odds?”

“There,” said Jane, snapping shut her computer. “Good 5G connection up here. Didn’t take long.”

“What didn’t take long?” said Deacon.

“Upload,” said Jane . “The world’s longest music video. It’s online. Remixed, edited together, finished. We did it.”

A few moments passed. The sound of DoneKirk pounded through the desert night.

They all stood up to leave.

“Just one more thing,” Deacon said, and he went to the utility box of the Airstream, returning with his ammo can and a shovel.

Overhead and overheard

The shovel kerchunked into the dirt. “It’s the end of the road for my ammo can,“ Deacon said. “All the stuff I had squirreled away in here, well, I don’t need it.”

Jane said, ”Forgetting. It’s all you need say or remember.”

Deacon patted the last shovelful of earth onto the mound.

“So, who said that?” Deacon asked.” Nietzsche? Kierkegaard?”

“Nope,” Jane said. “Jane. I just sort of saw that as you were digging.”

“Well, then, if you see shit like that you deserve these,” he said, and he handed Jane his night-vision goggles. She put them on just as Deacon lit a cigarette. The light from the flame nearly blinded her.

Jane coughed, wiped the lenses with her fingers, like a windshield wiper, and said, “Perfect.”

Pup’s screen test

And the band drove back into Sedona, found a discount campground, and slept in the Airstream and the back seat of the Caddy.

For the next two nights, D’Ray played a gig at The BallWash, a combo bowling alley/laundry that held about eighty people in the tiny bar section. Folks from the Burning Me concert came in, burned to the third degree and decompressing. On the second night, a young woman, who would normally have commanded Deacon’s loving attention, told him that his band should’ve been at the concert, that they were awesome and would’ve rocked the place.

Deacon said, “You want check out my collection of bootleg Velvet Underground vinyl, with Nico and everything?”

Sunday afternoon, the trailer was loaded, and they were ready to travel back to Michigan. Jane asked Deacon to drive … she wanted to get online. Pup sprawled in the backseat, munching on a twenty-burrito snack pack.

Jane cracked open her laptop and checked the band’s Youtube channel: Four million, three-hundred ninety-four thousand two-hundred and ninety-seven views, she says. And a few million new Instagram followers, too. She rubbed her eyes. The numbers stood. Her phone vibrates. Four messages. Odd, she thinks.

She listened. “Jane? Jane? Rob Stringer, Sony Music Entertainment. Call me.” Click. Then: “Jane, this is Jack Antonoff. Been checking out the music, the video. Gotta talk.” Click. And: “Miss Doe? Mandy Klein, executive assistant to Martin Scorsese. Marty would like to talk with you regarding your video.” Finally: “Jane, sweetheart, Rex Tremendae here. Long time no talk. You’re a genius. Call me at the home number; it’s on your phone.”

The heavily hybridized Cadillac

The sun blazed sweet and warm as the band motored down the ribbon-straight road, heading east to River Rouge. Plumes of road-dust rose behind, slowing changing into the shape of a huge devilish hand folding into a fist. The middle finger stuck up in the desert air, then faded in the breeze.

Above, a small saucer arced into a parallel path, escorting D-Ray home.